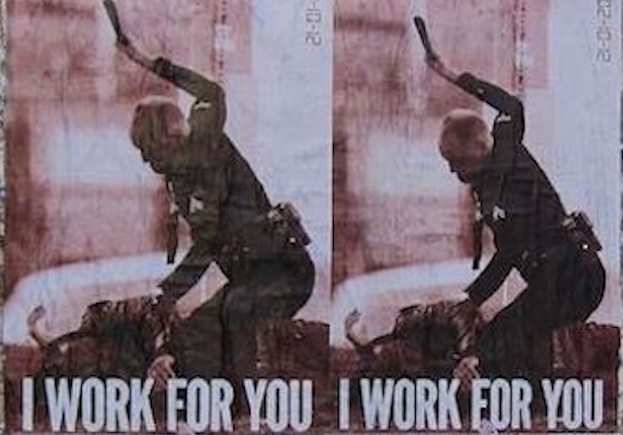

Court Denies NH Cop's Request for Qualified Immunity [law of the jungle status] after He Trolled, Searched and Seized a Truck Driver Washing His Truck at a Car Wash and Made Violent Unlawful Arrest

/From [HERE] An Ossipee, New Hampshire police officer failed in his bid to have an excessive force and unlawful arrest complaint against him dismissed based on his contention he is entitled to qualified immunity protection.

A federal judge found police officer Tyler Eldridge did not establish that he is entitled to qualified immunity and denied Eldridge’s motion to dismiss. Rather, the judge found that the officer’s detention, search, handcuffing, arrest, use of force and incarceration of plaintiff Brian Pearson were unreasonable and unlawful.

According to U.S. District Judge Paul J. Barbadoro, Eldridge apparently failed to appreciate that the immunity analysis at the early pleadings stage before trial is based on the plaintiff’s recounting of events as described in the complaint —and those facts describing his arrest of truck driver Brian Pearson at a local car wash were not in his favor.

Pearson alleged that Eldridge detained him without sufficient justification and used excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Facts Per Plaintiff

Late one summer night, Pearson drove his truck to a 24-hour car self-wash facility that offered self-serve vacuums and trash receptacles in a well-lit parking lot behind the car wash. Pearson parked next to one of the vacuums, took out some of his belongings and placed them on the ground nearby, and began cleaning the interior of his truck.

While Pearson was cleaning his truck, officer Eldridge sped into the parking lot, parked his police cruiser close to Pearson, and approached him. Eldridge immediately asked Pearson what he was “up to” and pointed to a baseball bat laying on the ground with Pearson’s other things. Pearson responded that he was cleaning his truck.

Eldridge then asked Pearson for some identification but before Pearson could get his driver’s license, Eldridge took out his handcuffs and told Pearson that he would conduct a pat-down search. When Pearson asked why, Eldridge told him to “relax.” After he handcuffed Pearson, Eldridge informed him that he was being detained because he was parked at the car wash late at night, had a lot of stuff around, was “animated,” and was not familiar to Eldridge. Pearson disputes that he was animated.

Eldridge then instructed Pearson to go to the police cruiser, lean against it, and spread his feet. After Pearson complied, Eldridge asked him for his name. Pearson did not respond at first, but he gave his full name when asked a second time. Eldridge then quickly gave Pearson the Miranda warnings. Immediately after, without provocation, Eldridge violently threw Pearson against the hood of the police cruiser. He held Pearson face-down on the hood, with his body weight on Pearson’s back and his hand on Pearson’s neck, until two other officers arrived on the scene a few minutes later. The encounter ended with Eldridge taking Pearson to a local jail under the pretext of taking him into protective custody.

Pearson eventually filed an action in state court, which Eldridge removed to federal court.

In his ruling, the judge explored the various stages of Pearson’s encounter with Eldridge.

Unreasonable Seizure

In what is known as a Terry stop, a police officer may stop and briefly detain an individual based on reasonable suspicion that the individual has committed, or is about to commit, a crime. The police may frisk a temporarily detained suspect if they have reason to believe the suspect may be armed and dangerous. Reasonable suspicion requires “specific and articulable facts” that would lead a reasonable police officer in the circumstances to suspect that criminal activity is afoot.

While a Terry stop requires only reasonable suspicion, taking someone into protective custody requires probable cause.

The judge concluded that the facts in the complaint establish that Eldridge conducted an unlawful Terry stop and frisk. Contrary to Eldridge’s suggestion, a reasonable officer in his position would not have suspected that Pearson was loitering at the time of the stop. There was no indication that Pearson had engaged or intended to engage in an activity that threatened public safety. Pearson was patronizing a business during its regular hours for the legitimate purpose of cleaning his vehicle.

The judge determined that the presence of a baseball bat, which Pearson had taken out of his truck with his other things and placed on the ground nearby before Eldridge arrived, was not enough to raise alarm. Under the circumstances, the only reasonable inference was that Pearson had taken his belongings out of his truck so that he could more easily clean the interior. Without more, a reasonable officer would not have believed that he needed to handcuff and frisk Pearson, the judge found.

Eldridge described Pearson as “animated” and told him to “relax.” But Pearson denied he was animated; instead, the complaint alleges that Eldridge’s assertion was a mere pretext for his actions.

Eldridge argued that he needed to ask Pearson twice for his name as evidence that Pearson had disobeyed a police officer. Pearson’s brief refusal to identify himself, however, came only after he was handcuffed. It, therefore, cannot provide justification for the Terry stop, the judge noted.

Accordingly, the judge concluded that qualified immunity cannot bar the claim that the Terry stop was illegal.

Protective Custody

Pearson also alleged that Eldridge violated his right to be free from unreasonable seizures when he took Pearson into protective custody. Eldridge argued that he had probable cause to believe that Pearson was intoxicated. Pearson alleges that Eldridge took him into protective custody under pretext and the judge found there were no facts from which a reasonable officer in Eldridge’s position could have believed that placing Pearson into protected custody was warranted.

A Fourth Amendment excessive force claim requires proof that “the defendant officer employed force that was unreasonable under the circumstances.” Courts must assess the reasonableness of a use of force “from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene” and must account “for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments — in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving — about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation.”

Pearson was handcuffed and compliant when Eldridge suddenly and without provocation violently slammed him against the police cruiser and held him pinned in that position for several minutes. According to the decision. Pearson had committed no crime and showed no attempt to resist or flee when Eldridge used significant force to subdue him. “In those circumstances, a reasonable officer in Eldridge’s position ‘would have taken a more measured approach,” the judge wrote, concluding that Eldridge used excessive force against Pearson.

Crediting Pearson’s allegations and drawing all reasonable inferences in his favor, “the level of force chosen by the officer cannot in any way, shape, or form be justified,” which precluded the qualified immunity defense at this stage, the judge wrote.

The case is Brian Pearson v. Tyler Eldridge, Case No. 21-cv-567-PB Opinion No. 2022 DNH 039.