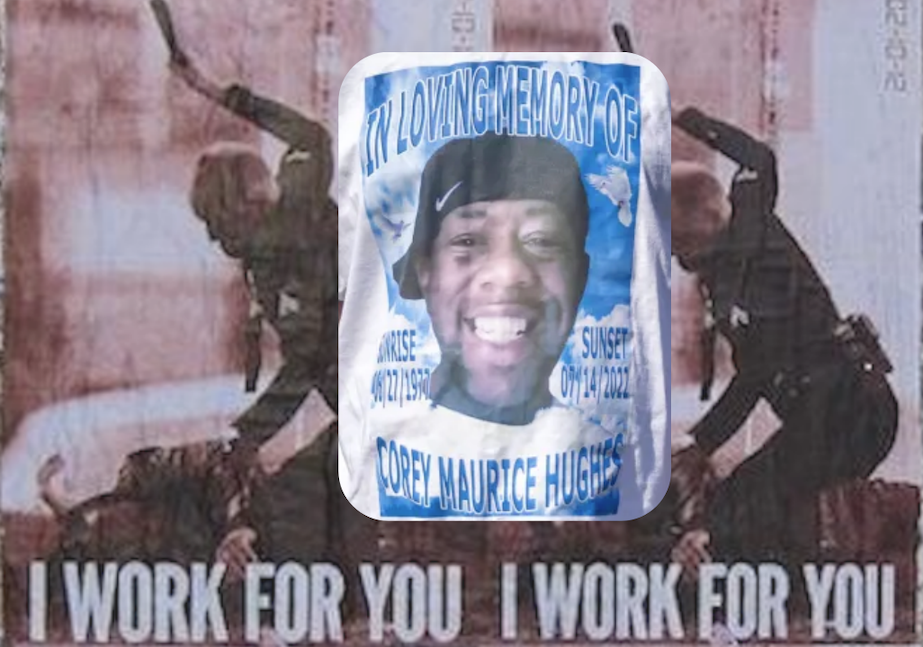

Shitty “Public Service” You Can’t Decline from Racist Suspect "Servants" You Can't Control: Gullible Black Family Called Forrest Cty Cops to Force Black Man to Take Medication. They Killed Him Instead

/From [HERE] If Corey Maurice McCarty Hughes stopped taking his medication, his family knew what to do. When he started to become paranoid or barricaded himself in a room, a family member would go down to the Forrest County chancery clerk’s office and file an affidavit stating that Hughes needed to be hospitalized. Then, sheriff’s deputies would pick him up and take him to get treatment.

The series of events had unfolded about 16 times before, and there was little reason to think it would be different when it happened again in mid-July of this year.

When family members sought to have him committed, they expected he would spend a few weeks or months at the state hospital in Purvis and then come home to Palmers Crossing in Hattiesburg, where he lived in a trailer a few hundred feet from his parents’ house.

On July 14, Forrest County deputies arrived at Hughes’ sister’s house to take him to the hospital. They killed him instead.

According to the incident report released to Mississippi Today by the sheriff’s office, Hughes struck a deputy with a “blunt object” before the deputy shot him in the torso.

Exactly what happened is still unclear: The Mississippi Bureau of Investigation is investigating, as it does every time law enforcement officers kill someone in the state. The Bureau refused to turn over records except for an incident report until the investigation is over.

The four deputies at the scene were not wearing body cameras; their department had begun buying the cameras only in June after receiving a federal grant. Forrest County Sheriff’s Office officials said they would not provide further information until MBI’s investigation is closed.

But to Hughes’ loved ones, the case is already a clear indictment of the state’s mental health and criminal justice systems, which are uniquely intertwined in a process called civil, or involuntary, commitment.

Every year, thousands of Mississippians and hundreds of thousands of Americans go through the civil commitment process. For some Mississippi families navigating a patchwork system of mental health services and care, having relatives forced into treatment is not just the option of last resort, but the only option.

Some Mississippians, like Hughes, go through the process more than a dozen times, cycling in and out of state hospitals without connecting to effective long-term treatment back home.

“Civil commitment is forcing someone to get mental health treatment,” said Sitaniel Wimbley, executive director of National Alliance on Mental Illness Mississippi. “Had that individual had someone to talk to … or they had been in a treatment plan, civil commitment may not be something that they ever have to see, because they would be aware of their mental health and what’s going on in the process to be able to get help for themselves.”

The state is the subject of a years-running federal lawsuit over its failure to provide adequate mental health services in communities, historically forcing people to spend years institutionalized in mental hospitals.

As in many states, Mississippi law specifically requires sheriff’s deputies to transport the person being committed, effectively forcing law enforcement to get involved in the care of people suffering from serious mental illness. The justification for this is that only law enforcement is equipped to physically force someone to get treatment against his or her will. But mental health advocates say the mere presence of a police officer – especially if they are not trained in helping people in a mental health crisis – can increase a person’s distress and agitation.

Hughes’ father, James Hughes, doesn’t understand why medical professionals were not on the scene – at the least to talk with his son before police pulled out a weapon. On other occasions when he didn’t want to go to the hospital, officers sometimes used their taser, but never a gun, he said.

“I’m under the impression, well, I’ll be going to Purvis to visit my son,” he said. “And then I have to bury him.”