Georgia's Scheduled Murder of Unarmed, Restrained, Retarded Black Man for Revenge ["the death penalty"] is straight from the theater of the absurd

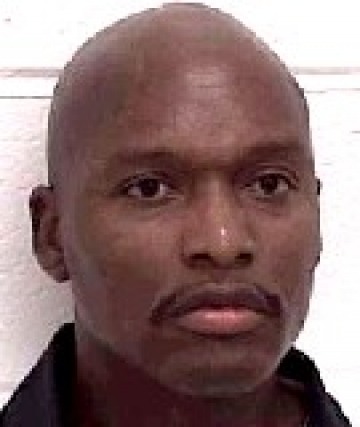

The Rule of a Barbarous Society From [HERE] The LA Times editorial board Friday weighs in on the absurdity of the state of Georgia’s efforts to execute convicted murderer Warren Lee Hill Jr., who faces lethal injection next week despite expert witnesses for both sides who now say he is intellectually disabled and thus ineligible for capital punishment.

An aspect of the case that went unexplored in the editorial is Georgia’s unreasonably high bar of proof for intellectual disability. According to Hill’s legal filings, all states that still have the death penalty have a “preponderance of the evidence” hurdle to proving intellectual disability. Under that standard, a condemned person is entitled to leniency if most of the experts agree that he or she is intellectually disabled.

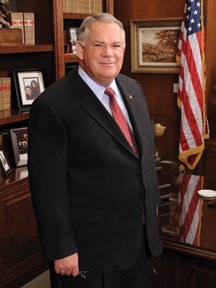

But in Georgia, the standard is “beyond a reasonable doubt.” That means if there is some disagreement among the experts as to whether the defendant is intellectually disabled, then the person doesn’t qualify for leniency and can be put to death. (In photo, racist suspect, Georgia House Speaker David Ralston who told WABE, "our death penalty laws, to my knowledge, have been upheld as constitutional to this point. I don't know that there needs to be a national sort of standard in these cases." [MORE])

So what’s the problem? The Supreme Court, in its Hall v. Florida decision last year, ruled that Florida had to look at other factors reflecting medical and professional standards in determining whether someone is intellectually disabled and thus ineligible for the death penalty under the 2002 Atkins v. Virginia decision. Part of the reasoning is that relying only on the narrower measure of an IQ of 70 or below (the accepted threshold) could lead to the unconstitutional execution of someone who is, indeed, intellectually disabled.

Hill’s lawyers have argued, so far unsuccessfully, that Georgia’s “reasonable doubt” standard similarly runs the risk of putting to death someone who has a constitutional protection against execution. And if Georgia’s standard was the same as the other death penalty states, Hill would be ineligible for execution. From Hill's petition:

Hill’s lawyers have argued, so far unsuccessfully, that Georgia’s “reasonable doubt” standard similarly runs the risk of putting to death someone who has a constitutional protection against execution. And if Georgia’s standard was the same as the other death penalty states, Hill would be ineligible for execution. From Hill's petition:

“Indeed, but for Georgia’s uniquely high burden for proving that a capital defendant is not eligible for execution on the basis of intellectual disability, Mr. Hill would have been found intellectually disabled in state habeas proceedings and would not be facing execution today.

“In initial state habeas proceedings, the state habeas court judge found that Mr. Hill’s IQ was approximately 70 beyond a reasonable doubt but that Mr. Hill had not proven his intellectual disability beyond a reasonable doubt because, even though his 70 IQ demonstrated significantly subaverage intellectual functioning, Mr. Hill had not proven sufficient deficits in adaptive functioning beyond a reasonable doubt given his history.

“In a subsequent order reversing its prior order and granting relief, the court noted that, were the burden of proof merely a preponderance of the evidence, it would find that Mr. Hill is intellectually disabled. The court’s findings and its rejection of Mr. Hill’s intellectual disability claim were affirmed on appeal and left undisturbed in subsequent federal habeas corpus proceedings.

“In a successive state habeas proceeding, litigated under warrant in 2012, the state habeas court again found that Mr. Hill had proven by a preponderance of the evidence that he is intellectually disabled, but had fallen short in proving intellectual disability by Georgia’s uniquely high burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Had Mr. Hill’s disability been assessed in any other State in the country, he would almost certainly have been found intellectually disabled and, thus, ineligible for execution.”

And notably, the testimony that led the courts to rule Hill had not cleared the "reasonable doubt" threshold has now been recanted. Those who had sowed the doubt now say they were wrong. Yet Hill still faces execution.

Ironically, Georgia was ahead of the curve when it comes to recognizing the impropriety of executing the intellectually disabled. It banned such executions in 1988, four years before the Supreme Court’s Atkins decision made it the law of the land. But when it enacted its ban, Georgia created its indefensibly high burden of proof. In the face of the conundrum presented by the Hill case, the state Legislature ought to revisit the issue and bring Georgia's standard in line with the rest of the death penalty states.

Or maybe even go a step further and ban the barbaric practice entirely.