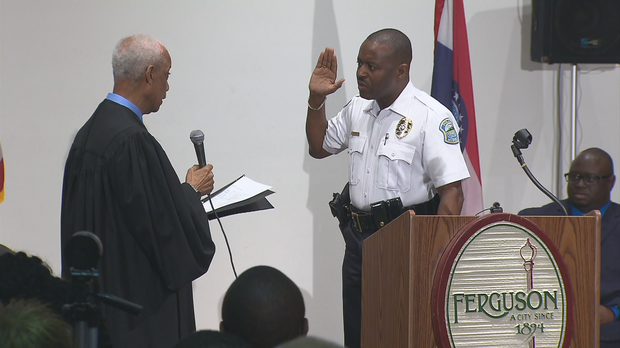

[Racism is Carried Out By Various Pretenses that Depend Upon Our Belief] Ferguson Case Raises Doubts About Reform

Only The Appearance of Justice. In photo, new Black police chief in Ferguson is sworn in by a Black judge. [MORE] Unbeknownst to both men, they are stage props, part of the necessary illusion of the appearance of justice and the myth of progress in a system of white domination & control.

From [HERE] When the Justice Department issued a scathing report that detailed routine civil rights violations by the police and courts here after an officer fatally shot Michael Brown in 2014, one anecdote generated particular outrage.

A black man was sitting in his car in a Ferguson park when a police officer drew his gun on him. The officer searched the man’s car without permission and wrote him more than half a dozen tickets, including for lacking a vehicle inspection sticker and not wearing a seatbelt, even though the car was parked.

The episode, which occurred in 2012, helped spur the city to agree to criminal justice reform, and, along with the Brown case, prompted a federal consent decree with the Justice Department in 2016.

But five years after the arrest, Ferguson continues to prosecute the man, Fred Watson, even as it struggles to repair its image as a city that has been unfair, and at times hostile, toward African-Americans.

Mr. Watson is due in court on Tuesday for the start of a criminal trial for nine minor charges stemming from the episode.

“When does it stop?” Mr. Watson, who lost his job as a defense contractor after the arrest, said through tears during a recent interview. “This goes way beyond me. This practice has got to stop.”

The continued prosecution of Mr. Watson, 37, has raised questions among some residents about how serious Ferguson is about reform. The shooting death of Mr. Brown brought scrutiny not only on the frequency of police officers’ use of force against unarmed African-Americans, but also on Ferguson’s municipal court system and the practice, nationwide, of employing courts to bring in revenue through fines and fees.

Criminal justice officials in Ferguson would not discuss why the prosecution of Mr. Watson had moved forward, despite what appear to be numerous problems with the case.

City officials, however, say Ferguson is well on its way to change, particularly in its municipal court system, which came under harsh criticism by the Justice Department.

The city said that since August 2014, it had dismissed 39,000 municipal court cases, forgiven $1.8 million in fines, and enrolled 1,381 people in community service projects instead of requiring them to pay fines.

In addition, since the death of Mr. Brown, the city has replaced its police chief, municipal judge, prosecutor and city manager. Those former officials are white, although Ferguson is more than two-thirds African-American.

De’Carlon Seewood, who was named city manager, and Lee Clayton Goodman, who became the city’s prosecutor, are part of the new generation of Ferguson leaders brought in to overhaul the criminal justice system and to meet the provisions of the consent decree. Both are African-American and have lived in the area for much of their lives.

“We’re definitely moving forward,” said Mr. Seewood, who has been in his position since November 2015. “I don’t think a resident would say, ‘I’ve been treated unfairly.’”

But the city has nonetheless pursued Mr. Watson’s case with vigor.

Thomas Harvey, Mr. Watson’s lawyer, said Mr. Goodman had refused to drop the charges despite what he called problems with evidence, a number of errors made by the prosecutor’s office, and an arresting officer who, according to state records, has a history of beating suspects and falsifying reports.

“None of it makes sense,” said Mr. Harvey, of Arch City Defenders, a nonprofit civil rights law firm in St. Louis that is handling the case.

Mr. Goodman, who inherited Mr. Watson’s case from the previous Ferguson prosecutor, did not respond to requests for an interview.

Mr. Watson, who joined the Navy after high school to study cybersecurity, was born in St. Louis. He said he was well aware of the hazards of being an African-American male in St. Louis suburbs like Ferguson, and took care to follow traffic laws and to ensure that his brake lights worked.

His precautions did not help.

On Aug. 1, 2012, after playing basketball with friends in a Ferguson park, Mr. Watson said he walked to his car, where he drank a cold bottle of water and switched on the air conditioner.

A few minutes later, the officer drove toward him and blocked his car with the police cruiser.

“He got out and asked me, ‘Do you know why I pulled you over?’” Mr. Watson said.

Mr. Watson said he was confused, given that his car was parked, although the engine was running. “The second thing he said was, ‘Give me your social security number.’”

Mr. Watson said he did not think it proper for a police officer to demand social security information. “I said, ‘No sir, I can’t do that.’”

The officer, who court records identify as Eddie Boyd III, grew confrontational, Mr. Watson said.

When he asked for the officer’s name and badge number, Mr. Watson said the officer refused.

And when Mr. Watson started to dial 911 on his cellphone, the officer cursed at him and ordered him to put the phone down, turn off the ignition and throw the keys out of the car, according to Mr. Watson.

Mr. Watson said he told the officer that he knew his constitutional rights, and refused.

The officer then pulled out his gun, Mr. Watson said, and told him: “I could just shoot you right here and no one would” care.

Mr. Watson said he put down the phone and grabbed the steering wheel so his hands were visible.

“I’m thinking this could be the end of my life,” he said.

Officer Boyd, who remains on the Ferguson police force, and declined to comment for this article, has a troubled work history.

While serving as a St. Louis officer, Officer Boyd pistol-whipped a 12-year-old girl in the face in 2006, and in 2007 struck a child in the face with his gun or handcuffs before falsifying a police report, according to records.

The Ferguson Police Department also did not reply to requests for comment.

But Mr. Watson’s description of the incident is in line with details from the Justice Department report on Ferguson, which said officers routinely stopped people walking down the street, demanding to see their identification without probable cause.

In Mr. Watson’s case, the arrival of other officers defused the situation, but Mr. Watson said he was arrested without having been informed of his rights or told why he was being arrested.

He was initially charged with seven violations: driving without a license, lacking proof of insurance, failure to register the vehicle, lacking an emissions inspection sticker, not wearing a seatbelt, driving with an expired license and having tinted windows.

Mr. Watson said that when he complained about the arrest, the police added two more charges: failure to comply with a police officer and making a false report.

The false report charge was added because Mr. Watson provided a different name from the one on his license.

“He said ‘Fred,’ instead of ‘Freddie,’” said Mr. Harvey.

Weeks later, when he appeared in court, Mr. Watson said a clerk told him there was no record for him in the system and asked him why he was there.

Since then, the case has been beset by delays. At one point, the prosecutor’s office sent a letter to Mr. Watson’s lawyer stating that all charges against Mr. Watson had been dropped. They were later reinstated.

Mr. Watson said the city’s dogged prosecution had sunk his family into poverty after he lost his security clearance and was fired from his cybersecurity job, which paid more than $100,000 a year. Until his arrest, he was a government contractor with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, which provides intelligence and research to the Defense Department and other agencies.

He said he suffered from bouts of anxiety, feared leaving his house because of potential police harassment, and did not answer the phone to avoid debt collectors.

“This is a stain,” he said of the effect of the arrest on his career. “This is always in your record. I don’t know that I’ll ever recover.”

Critics of Ferguson’s criminal justice system say Mr. Watson’s case illustrates the city’s lack of will to completely embrace reform. The City Council initially rejected the consent decree, saying its provisions were too costly, and the city has since missed a number of deadlines related to the agreement.

Brittany Packnett, an activist and former member of the Ferguson Commission, the group formed by then-Gov. Jay Nixon to study the city’s disparate social and economic conditions after Mr. Brown’s death, said the process has been sluggish at times.

“It is a reminder of how slow the pace of change can be, and ultimately, how deeply entrenched the systems we are fighting are,” Ms. Packnett said. “Those systems were not built in three years, and we’re not going to get rid of them in three years.”